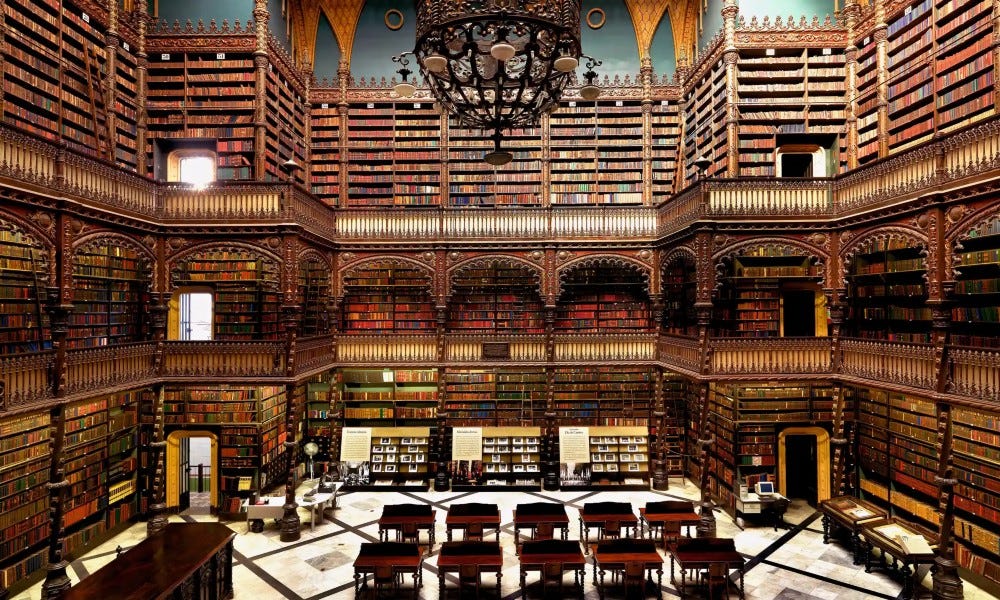

Real Gabinete Português de Leitura, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The low clamorous murmur of a hundred respectful whispers, the heady scent of wood, heavy under hand, expertly polished, soft leather undertones, the rough hewn scuff of the turn of a page, the squeak of a chair, a pencil softly clattering to the floor, embossed gold lettering faded under years of curious thumbs, encoded numbers.

I love libraries so much I wish I lived inside one. A sacred space. Something secret to be let in on — knowledge maybe?

I have wanted in on that secret for as long as I can remember. I learnt to read when I was incredibly young. Not because I was a child prodigy but because of a natural aptitude for something that I did nothing I’m aware of to cultivate though it is one that serves me extraordinarily well in my chosen profession — I can memorise literally anything. I really can. I have an exceptional memory. At drama school, my friend would grant me a weekly task of memorising 12-digit numbers and gleefully ask me to recall them a week later. I call it my super-power though it doesn’t always serve me. Letting go can sometimes be harder because of it. More than one ex has referred to me as Memory Girl, for good or for ill. Photographic? Maybe. Although someone once told me that that isn’t actually a thing. I can vividly remember shapes on a page, a person’s face, a logo.

Have you ever been looking for something you’ve seen before in a book and you can picture not only the side of the book the page is on, say left or right, but also the layout of that page, say if it was a half page of text before a chapter break, and then its precise position within that page, say middle of the second paragraph? If any of that speaks to you then I think you have a photographic memory too. Or maybe that’s how we all do it and it’s just called, having a memory. I’ve certainly never known anything different. It’s why I adore poetry but loathe hearing it performed or read out loud. To me poetry belongs on the page because part of its art-form is the shape that it is written in.

Before I could actually read, I pretended I could. My mother collected comedy screenplays and call it prophecy or an education, I used to sit propped up with a copy of Yes, Minister on my lap. I would scan the tightly packed symbols in front of me, as illegible as hieroglyphics, desperately searching for meaning. I would turn the pages after what I thought was an appropriate amount of time to prove to my parents that I was making progress. An early form of acting? I don’t know if I was trying to emulate something I’d seen an adult doing, or maybe a past life bookworm was compelling me to remember the skill but I was obsessed with being able to read. Around the same time I memorised my favourite children’s book, The Cat on the Dovrefell - a Norwegian folk tale about trolls and feasts and Christmas. I made my father read it to me every night, no matter the season, over and over and over, and at some point by osmosis I’d retained every word of it. I couldn’t yet read but my confident reciting of the book coupled with my Yes, Minister fascination was enough to trouble my parents into thinking that maybe I could. In fairness, perhaps just by sheer will, my actual ability to read followed shortly after.